The Battle of Gaugamela

On October 1st, 331 BC, one of the decisive battles in world history took place. The battle of Gaugamela formed the highlight of Alexander’s campaign. After Darius III lost the battle in his first encounter with Alexander the Great at Issus (333 BC), in order to avert another war, he offered Alexander the surrender of all areas west of the Euphrates, a high ransom for the harem captured by Alexander at Issus and the hand of his daughter in marriage. But Alexander refused. His goal was to conquer the Achaemenid Empire.

One day, scouts reported that Darius had begun to assemble a massive army by the Euphrates. Darius was now ready to lead the decisive battle, but Alexander wanted to wait until Darius had recruited the very last Persian. In this way, Alexander wanted to ensure that a further battle would not be necessary.

Alexander’s army consisted of 40,000 infantry men and 7,000 horsemen. Compared to the Persians, he was at a clear numerical disadvantage. But his army consisted predominantly of hugely experienced veterans, and the short chains of command would be useful in battle. His army consisted of the Hetairoi cavalry, who were armed with spears. The Hypaspists, similarly-armed to the Greek Hoplites, but not as limited in their movement. Alexander also had the Pezhetairoi, who were armed with extremely long spears and the usual lightly-armed troops in his army. Alexander’s father Phillip had assembled a mighty army from a slack original squad, on which he could now rely. His army was joined by many allies and soldiers from Greece and the entire Balkans. Alexander had also learnt from his father to only use the infantry for defensive purposes and to wait for the right moment to then launch a personally-led attack with his heavy Hetairoi cavalry. As with the Battle of Issus, this attack should also help to him to victory.

After Darius’s defeat at Issus, he had almost two years to build up an army. In order to achieve numerical superiority, he recruited every man of fighting age in his empire. But many of these men were poorly or barely educated, which in the end led to a mass panic. The army of the king consisted of many different tribes mixed together. Foot soldiers and horsemen from Mesopotamia, Babylonia and from the coasts of the Persian Gulf. Darius’s army comprised at least 250,000 men, among them 30,000 Greek soldiers, 12,000 heavy Bactrian horsemen. Unlike the majority of the army, the cavalry was made up of many experienced fighters, its core, the kara (general call to arms), was permanently armed. The Indians made 15 war elephants available for the battle. And 200 of the feared scythed chariots were to be used. These were supposed to break up the Macedonian Phalanx during the battle. In addition there was also the royal guard, including soldier units of Greek Hoplites. After Darius had assembled his army, he scouted around for a suitable battlefield. He wanted to make use of his numerical superiority, with the result that Alexander would be forced into the wide plains of the Tigris to do battle. The king ordered one of his officers to watch for the approach of the enemy, but to let him pass by undisturbed. Alexander was to cross the Euphrates with his troops unhindered. He himself headed from Babylon in a northern direction. At Arbela the king pitched a camp, from there he positioned his army in the plains between the Tigris and the Zab. Darius had these plains cleared of all unevenness, so that the scythed chariots could be used to full effect. Alexander’s goal was the centre of Mesopotamia, at Thapsakos he led his troops across the Euphrates and then turned to the north-east. As soon as it was reported that the Persian army had arrived for battle just a few days’ march to the south, in the plains of Gaugamela, Alexander set up camp immediately.

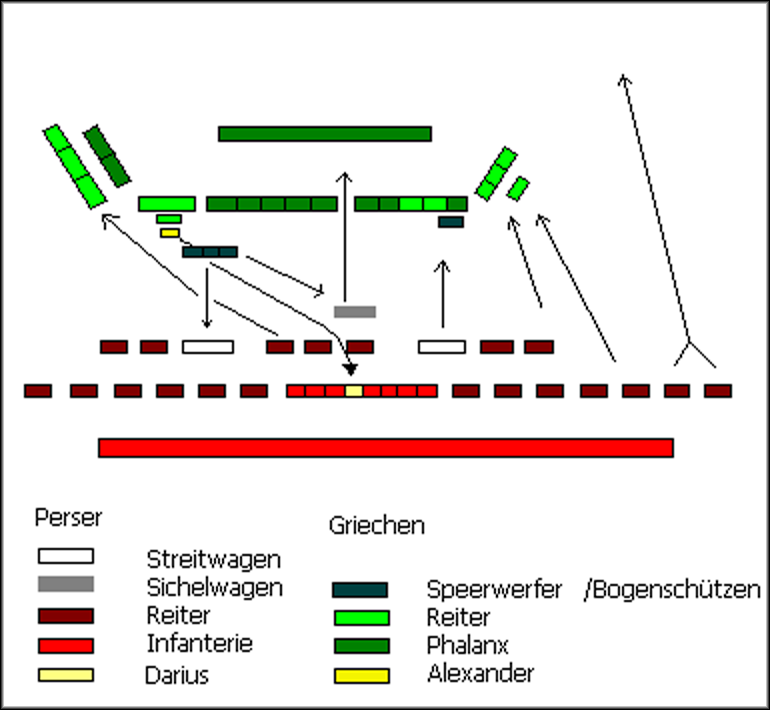

On account of his numerical advantage, the favourable terrain, the scythed chariots, war elephants and fighting power, Darius was very sure of victory, but the Persians feared a night attack by the Macedonians and therefore ordered all men to remain awake, in order to be prepared for an attack. Parmenion planned such an attack, but was restrained by Alexander. He prepared his plan of attack during the night an allowed his men to rest. The plan included some improvements to the formation. As Alexander had to face the size of the Persian frontline with an encirclement of the Macedonian flank, he positioned a second troop division behind the phalanx of sarissa-bearers. These were instructed to double back during the encirclement, so that a square shape would be created. The Persian front consisted mainly of cavalry, and was supported to the right and left by scythed chariots. Between these were some individual infantry. However these were mainly concentrated with the elephants in the middle. As at Issus, Darius stood with his guard behind the centre, with the Babylonian infantry behind him for additional protection. This hierarchy brought the formation of the Persians to a length of 3 – 4 km. Alexander positioned his phalanx of sarissa-bearers in the centre and allowed the Hetairoi cavalry, led by himself, to take up the right flank. Alexander positioned the flexible Hypaspists between the horsemen and the phalanx. His left flank was occupied with the Thessalian and Greek cavalry, under the command of Parmenion. Behind the phalanx he positioned as planned a troop of lightly-armed cavalry and infantry. Alexander’s plan was very audacious. He wanted to lure the heavy Persian cavalry away from the centre by attacking the flanks, in order to then lead a mounted attack on Darius III through a hole in the centre.

The battle began tentatively at first, then Alexander tried to find a favourable attacking point against the scythed chariots through an improvised movement. He extended and thinned out the right flank. The king expected a lateral attack and ordered the horsemen on the left flank to attack, so that a grim mounted battle took place. The hoped-for advantage from the scythed chariots never materialised. First, the lightly-armed soldiers decimated the charioteers with spears, then the phalanx formation opened to allow for the unhindered passage of the chariots, which were then annihilated in the background. But the king’s troops put the Macedonian phalanx under severe pressure and Alexander suffered heavy losses. But due to the advance of the Persian left flank, the Persian formation quickly fell into disarray. Darius was now only covered by his bodyguards. At this moment, Alexander launched the attack on the Persian centre with his cavalry, coming dangerously close to Darius. He fled, although the battle was not yet over for the Persians, the resistance of his guard was of no avail, and he feared being killed on the battlefield. The flight of Darius was interpreted by his men as a sign to retreat, shortly thereafter the entire Persian front collapsed. But the fleeing king could not be captured by Alexander. After his victory, Alexander declared himself with great pride the “King of Asia”, and Darius lost his legitimacy following his flight and was later murdered by Bessus.

Youtube-Link: Battle of Gaugamela, 2 parts (english)